Making Irrealis

May 27th, 2022DÉBUT

FRIENDSHIP, COLLABORATION, AND THE UNREAL

These pieces were made barely moments after recording a piece for another project – caught impulsively, but also on the precipice of velleity from which much of my work seems to emerge. There is a liminality to these proceedings, but on the conclusion of each piece, there seemed an impetus to continue onto the next, and again to the next. Recorded in one sitting, these seven pieces are meditations of a sort, each possessing an implicit musical character that is dedicated to those individuals to whom I feel the music belongs.

My own Public Relations blurb above is not an accurate account of how the music came into being. The following is an attempt to discuss the resulting music through the mechanisms of friendship and collaboration, the slippery meaning behind the album title, the whys and hows of deciding on whom to gift my music; and how the physicalisation of all this was mirrored in the making of the album artwork.

INTERIORITY LEADS THE WAY – Robert Bresson

All of this started way back (exactly ten years ago), when a gentleman came to buy a synthesiser from me on a particularly hostile evening, clutching a cache of records under his arm… Little did I know that this was Glenn Armstrong – aesthete, curator, producer, founder of Coup D’Archet record label, lovely human being. I had no idea that this meeting would also lead to a very dear friendship, and even less that we would collaborate on one of the most unique and extraordinary projects I’ve ever been involved with. The work in question (let’s call it Project S) is firmly under wraps for the time being, but I’m mentioning it here because it is precisely the journey of our friendship, and of the ups and downs of making work together that led directly to the music on Irrealis.

In short, these pieces resulted because of a failed attempt to remedy a wobbly track, and to divine a similar spirit to the Project S recording sessions that had taken place some twelve months prior. Although this track fix was out of my reach, it was the weight of experience only an intense immersion (of many years) in a substantive project that brought about the setting in which this music could emerge.

I owe much to the assignment of my collaborator in that these pieces are succinct, impulsive, and are contrasting in narrative, melodic sensibility, and harmonic character to the subject of Project S, and emerge from a quality of lack, or absence. My view here is that music is more of an appearance from a reassembled table of contents, or scrobbled inventory of experience. It is a meshwork of practice, communion with the piano, thinking, listening, and refining or building through abstract means, those links and bridges between disparate ideas; and sometimes of holding on to the threads of things heard and noted years ago, only for them to reemerge, refracted through the physicalisation of performance in the present. By acknowledging an absence of intent (velleity), I also acknowledge the Catch-22 that Irrealis was only possible due to the significance of friendship(s), and the weight of preceding simpatico collaborative work (not to mention the consumption of a shit-ton of Co-Op Viognier, C19th literature, art, discussions about modernist furniture, Full-English breakfasts, Alfred Deller, 1960s/1970s British Jazz, Samson François, and rare vinyl heard through some of the finest valve HiFi amplifiers courtesy of Gary Wood).

With all of this now in focus, what follows is a brief account of how these things are realised through performative mechanisms.

COMMUNION

With the piano already prepared, failed attempts recorded – the seven consecutive improvisations that followed capture the sound of exploring a new instrument for the first time. Placing foreign objects on/in between the piano strings is not my usual style – preferring the limitation of bare hands and the possibility of bloody injury…

Pianist and composer Keith Tippett was someone who also favoured the alteration of a conventional piano sound to introduce different ‘characters’ into a performance – his own solution to the problem of ‘fixed’ preparations (the insertion of screws, nuts, bolts etc. can be time consuming to set up, and almost as long to remove, depending on the situation), was through utilising light pieces of wood, large pebbles, music boxes, plastic toys etc., that could be easily placed/removed. Here though, I approximated the setup from the original Project S sessions:

PROJECT S

IRREALIS

THE FIRST IDEA

Each of the pieces begin with what I refer to as the first idea, which is simply a way to describe the act of surrender by deliberate listening to whatever sound(s) arise in the first instance, intentional or otherwise (it is often those which arise unintentionally that are of most use or interest to an improviser). It’s a kind of bearing witness to sound, and then committing to following its lead over any preconceived ideas that might have arisen otherwise. In addition, the piano on Irrealis was only prepared from the middle C key upwards (the lowest note in the aforementioned Project S piece). Aside from Jane, all of the pieces are played with middle C as the lowest note – with the reduced range providing useful limitation.

TITLE

Irrealis is a grammatical marker / set of linguistic moods that refer to any clause that may be imaginary instead of actually true / indicate action(s) that are not known to have occurred at the moment the speaker is talking. It is also the title of a poem by Dorothy Lehane, taken from Places of Articulation (Dancing Girl Press, 2014). The following paragraph retrospectively forces a definition onto the music – creating a bullshit narrative which implies that I chose this word deliberately – over simply appropriating it because I liked its ambiguity and irrelevance:

Irrealis also describes, in a lateral sense, my own process of musicking – where personal communion with, or escape, into the intangible / invisible world of sound is a place of unconditional trust and truth. I cannot however commune and receive simultaneously. It is only through recording, and listening afterwards, that a temporary glimpse into this irreal universe is possible, where the outcome often appears imaginary, or dream-like in the real world. And whilst we’re at it, these pieces are also an expression of sonic unreality; a hybrid created by an interdependence of conventional piano architecture, some Blu-Tack, and a few packs of M6 roof bolts from B&Q.

DEDICATION

I’m rather fond of dedicating or gifting my work to those who are/have been significant to me (most often the latter), extending to anyone who has had an involvement in or around the time of making the music, listed under ‘personal gratitude’ somewhere on the album sleeve(s). The process usually involves listening to any given piece several times until it evokes the idea of something, or someone – followed by a shortlist, then leaving it for a few days until making the final decision. A while ago I figured that most titles of anything are always abstract, and so why not be named after people? My official quip about dedications is that you don’t want one – with most dedicatees being either ex-girlfriends or dead (but curiously never a combination of both). There are however exceptions to this rule, especially in Irrealis, where the ratio of ex-girlfriend/dead : living is 2 : 7.

- Shri Siram, Asaf Sirkis and Dušan Petrović are all musicians I played with during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, journeying to Romania to play at the 2020 Gărâna Jazz Festival;

- Jane is for my mother;

- Laurent Dehors is a kindred spirit. I love him dearly, and feel blessed to have known him and played so much incredible music with him over the last sixteen years;

- Alice is an ex, yet thankfully we remain friends;

- Armando is dedicated to the late pioneering jazz pianist Armando Anthony ‘Chick’ Corea – I’ve long enjoyed his music, and this dedication is made on account of the presence of some ‘Chick-sounding’ right hand phrases.

ART

SPLIT & THE PEOPLE POWERED PRESS

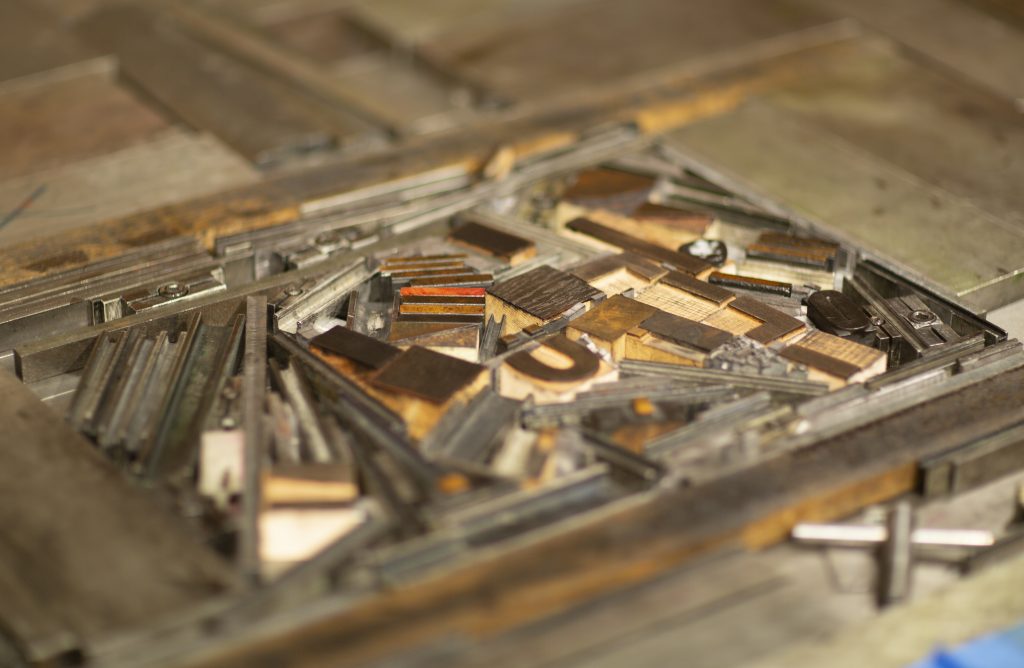

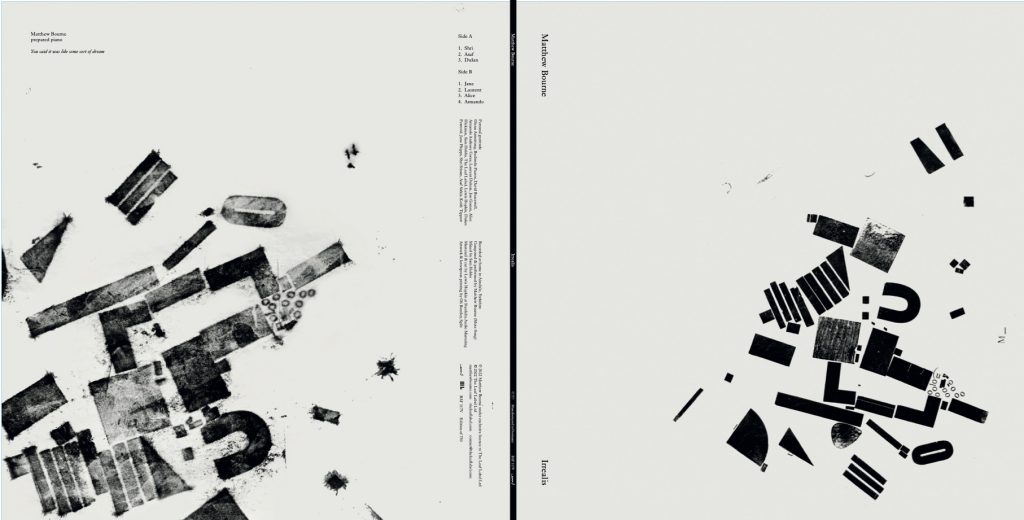

Oli Bentley is founder of Split, an independent design studio based at Salts Works, West Yorkshire – and is also home to the largest letterpress in the World – the People Powered Press. Oli wanted to make a letterpress printing that mirrored the quick, impulsive approach to preparing the piano and making the music, and thus used a selection of wood and metal type, and other letterpress wood blocks – all originally destined for use in other ways. The design was made entirely in the bed of the printing press, and without any sort of digital mock up or design beforehand.

If you look closely, you can also see guitarist/vocalist Jon Gomm’s very own signature plectrum. Jon is an old friend, and he just so happened to be crossing the road outside. This serendipitous meeting meant that he had to be involved: creative work as an extension of human relationships…

You said it was like some sort of dream

(how are you at endings?)

FIN